Melissa

Kaplan's

Herp Care Collection

Last updated

January 1, 2014

American Trader Oil Spill

February 1990, Huntington Beach CA

Because of my background in animal behavior observation and medical terminology, I was assigned to the 'hospital', the area in the facility where the most critical birds were kept. Since brown pelicans were on the California Threatened Species list, it would have cost the oil company responsible for the spill $150,000 per dead pelican...so the care they got was intensive.

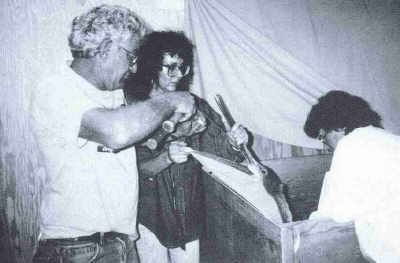

Force-feeding oil-spill brown pelicans at IBRRC's Terminal Island, CA rehab facility. Photo by Marge Gibson/IWRC

In addition to the rehydration (300 cc warmed Pedialyte, 6 x daily), forced feeding (300 cc warmed seabird slurry*, 6 x daily) and medications to detox, reduce stress, and fight bacterial infections given to all sick birds, the seriously ill pelicans had to be hooked up to intraosseous lines to administer 1000+ cc of saline per day, making administering food and medication quite interesting... It took four people to feed each pelican: one to hold the 5 loaded 60cc syringes, each with a feeding tube attached; one to hold the pelican's body; one to hold open the beak, and one to quickly grab the syringe, insert the tube carefully past the pelican's glottis, express in the mixture or Pedialyte, hand the emptied syringe back to the person holding the rest of the syringes, grab another and do it all again - five times per the often dozens of pelicans we had each day in the hospital, 6 times a day. It had to be done as quickly, but as smoothly and quietly and apparently calmly as possible to keep the stress levels down as far as possible for the pelicans who were already under a great deal of stress.

*The slurry was Purina Trout Chow soaked in warm Pedialyte, mixed with various vitamins and some vegetable oil. This was warmed in the microwave just prior to use. Because of the rapidity with which this mixture spoiled, even when refrigerated, we had people whose job it was every day, all day, to just make slurries for all the birds.

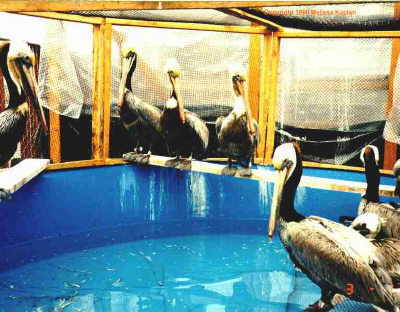

One of 6 feedings and 6 hydration events occurring each day for each of the brown pelicans in the recovery facility run by the International Wildlife Rehabilitation Council under contract to British Petroleum whose oil was being transported by the American Trader tanker.

We also had American coots, surf scoters, several species of sea gulls, grebes and a couple of cormorants. All of these birds only required two-person feeding teams: one to hold the bird and open the beak, and one to do the actual feeding or rehydration.

The sheets were draped over the pelicans, as with the other seabirds, to reduce their stress in the facility. The tenting for the pelicans was to accomodate their height when they sat and stood up. You can see one of the IV bags hanging on the wall between the first two tents. Photo by Melissa Kaplan.

For the pelicans, it was probably a bit of hell on earth until they were strong enough to be washed to get the oil off of them, detoxed to get the oil out from inside of them, and progress to the "well room", the last step before being allowed outside during the day.

Product of choice to remove crude oil from birds? A 1% solution of Procter-Gamble's Dawn dishwashing liquid soap.

Some of the pelicans, enjoying the wintery February sunshine. The spill happened while many shore birds were overwintering in the nearby Bolsa Chica estuaries and wetlands. Brown pelicans spend the winter down in Baja and Southern California. Photo by Melissa Kaplan..

Outside was the waterproofing enclosure where they were fed fish and provided tubs of water and roosting facilities during the day so they could re-waterproof their feathers while being observed by staff to make sure they were functioning properly. Once they were strong enough, they were allowed to sleep outside at night, until the time for the next release.

Before being released, all pelicans were banded with a metal U.S. Fish & Wildlife band, and a bright plastic tag that had a number clearly printed on it. This was so that periodic observations could be made of those released as they mingled with those who escaped the spills, as they moved up and down the western coast of Baja and California throughout the year...and so that deaths could be recorded, assuming citizens who found dead banded birds actually reported them to state or federal wildlife agencies.

This pelican is busy waterproofing his feathers, using his beak to straighten and align all his feather quills and coat them with body oil birds produce through a special gland. His yellow plastic identification tag is barely visible behind his spread tail feathers. Photo by Melissa Kaplan.

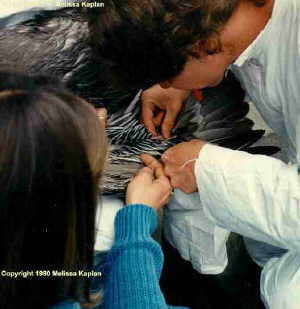

Because of the threatened status of brown pelicans, the head of the Wildlife and Fisheries Department and the University of California, Davis, came out and selected 20 pelicans who were then outfitted with radio transmitters. Data was collected on these birds, including taking blood and cloacal swabs for later analysis, and the birds' weights. The harnesses and radios were lightweight. The batteries last about 12 months and the harness is affixed with a glue that will slowly degrade, so they will fall apart - and so off the pelican - a short time after the battery dies.

Here, a vet tech is drawing a blood sample from a pelican who is about to have a radio transmitter attached prior to its release. Photo by Melissa Kaplan.

All of the stress and strain, long hours, and feelings of sorrow for every bird brought in dead or too far gone for our ministrations to be of any use were lightened when we were able to go on a release - when our now former patients were set free to return to their wild lives. When I was running the feeding teams, I made sure that all the volunteers went on at least one release, to help them balance the devastation of the spill with the positive outcome: a bird flying free once again.

Free at last! The joy on the volunteers' faces mirrors, we believe, the birds' feeling of being released back into the wild after several weeks or more in the oil spill recovery facility. Photo by Melissa Kaplan.

The first couple of releases were apparently big news around the contry. Several television stations and newspapers sent news crews out to record the event. My father even got calls from a friend outside the U.S. who recognized me when they saw the film on CNN.

Newsday at the release site. Photo by Melissa Kaplan.

Me, in February 1990, before my descent into the abyss known as CFS, FM and MCS. How prophetic that the photo was taken at the oil spill recovery facility at the too-aptly named Terminal Island.

If you are interested in training to be a wildlife rehabilitator, or in volunteering to work at oil spills, contact the International Wildlife Rehabilitation Council (IWRC) in Suisun, California, for more information. For information on brown pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis), you will find some at the US Fish & Wildlife Service's Species Biologue and and Status Summary sites. The California subspecies, Pelecanus occidentalis californicus, is still on the state and federal endangered species list. I also had an opportunity to work with American white pelicans (P. erythrorhynchos) in Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge and the nearby Lower Klamath NWR, which included an incredible early morning hike through and small boat trip across the Clear Lake NWR to catch, band, weigh, and take fecal swabs of the white pelicans nesting there.

Related Articles

Crude Awakenings: Could an Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Happen in Southern California?

Attorney General Lockyer Announces $16 Million Settlement for American Trader Oil Spill

Post-Release Survival of Oil Affected Sea Birds